Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII)/Perplexing Presentations

Scope of this chapter

This chapter contains information about the approaches and legal frameworks which should be used to support children and young people who are at risk FII.

Amendment

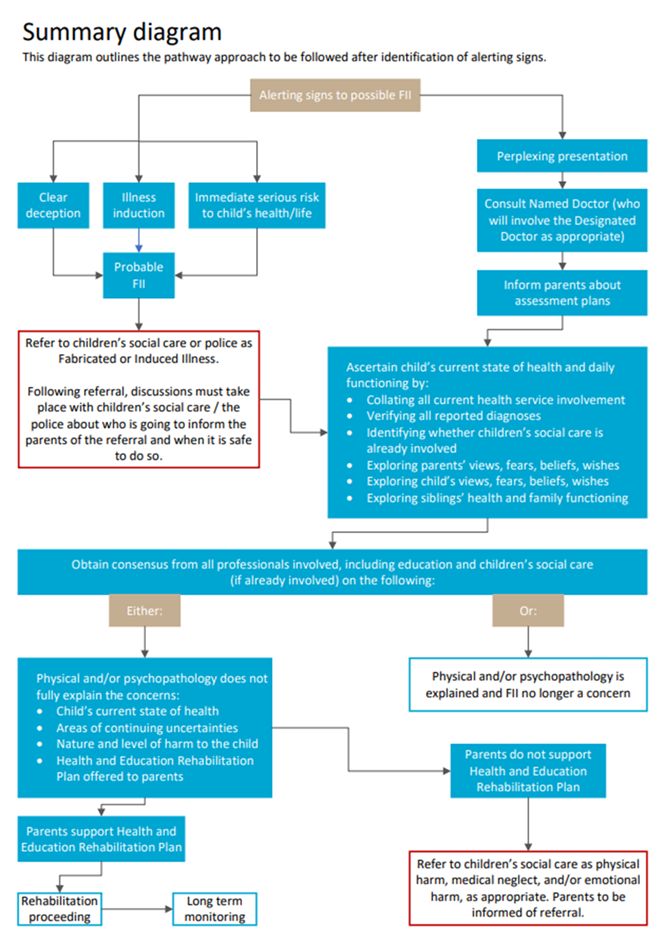

The chapter was revised in September 2025 and should be re-read. All SPB Jersey Core Procedures and Practice Guidance is underpinned by the Children (Jersey) Law 2002, Children and Young People (Jersey) Law 2022, commensurate Statutory Guidance and the JCF Framework. This chapter has also been revised in line with RCPCH Summary Guidance 2021 to include the definition of FII and the inclusion of Perplexing Presentations. There is Summary Guidance in the form of a flow chart. The chapter is also updated to include Practitioner Guidance on the use of the Continuum of Children's Needs, JCF Multi-Agency Chronology, Supervision and Professional Difference/Escalation Policy.

Fabricated or induced illness (FII) is a clinical situation which occurs when parents or carers mislead health care professionals into believing that a child has a physical or mental illness or neurodevelopment impairment, which they do not have or that they are more impaired than they actually are. A small number of children are likely to be significantly harmed by the actions of their parents/carers in fabricating or inducing their illness.

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) launched guidance for paediatricians in 2021 on Perplexing Presentation and Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII), please see New guidance on perplexing presentations and fabricated or induced illness in children.

|

Perplexing Presentations |

The term perplexing presentation denotes the presence of alerting signs of possible FII when the actual state of the child’s physical/ mental health is not yet clear, importantly, where there is no perceived risk of immediate serious harm to the child’s physical health or life. |

|

|

Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII) |

FII is a clinical situation in which a child is or is highly likely to be harmed due to parents/carers' behaviour. FII results in emotional and physical abuse and neglect, including iatrogenic harm. Iatrogenic harm can occur where doctors (who need to) trust and work with parents who fabricate or induce illness. A child can also present with a health picture that is true, partially true or with mixed accounts that are fabricated or misconstrued, making it difficult to explore credibility. |

Synonyms Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy; Paediatric Condition Falsification; Medical Child Abuse; Parent-Fabricated Illness in a Child; (Factitious Disorder Imposed on Another, when there is explicit deception). |

The term "perplexing presentations" should be explained to both the child and parents, including a discussion around why there may be differing perceptions of the child's health between the parents/carers and the healthcare team. At this point, practitioners should avoid using the term FII, as the child's true health picture has not yet been fully assessed.

If concerns arise from school, a qualified school practitioner should inform the parents/carers that health-related information is needed to address concerns, such as poor school attendance. If the GP is the only healthcare provider involved, they should refer the child to a paediatrician for further assessment.

Practitioners must consider the child's well-being, health, development and welfare, making enquiries to the Children and Families HUB for support as appropriate (see Statutory Guidance – Levels of Need).

A multi-agency team, including the GP, paediatrician and Child and Adolescent Mental Health (CAMHS) services (if applicable), should work together to assess and understand the child's full picture of health, with the aim to work in partnership with parents/carers and to rule out the potential that the child’s perplexing presentation is linked to FII.

In working with cases of suspected FII, the focus must be on the child's physical and emotional health and welfare in the short and long term, and the likelihood of the child suffering significant harm.

FII may not necessarily result in a child experiencing physical harm, but there may be concerns about the child suffering emotional harm. They may suffer emotional harm as a result of an abnormal relationship with their parent/carer and/or disturbed family relationships (see SPB Jersey Recognising Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation). Some children who experience FII suffer significant long-term physical or psychological health consequences, and in extreme cases, they may die.

Clinical evidence indicates that FII is more likely to be carried out by: -

- The Child’s Mother or a Female Carer;

- The involvement of the father being variable, and they may be unaware, be suspicious but sidelined, (rarely but at times actively involved).

Safeguarding Children in whom illness is fabricated or induced (DCSF 2008

There are two recognised motivations:

- The parent/carer experiences gain (not necessarily material);

- The parent/carer holds flawed beliefs which are often anxiety-induced.

In FII, parents/carers' needs are primarily fulfilled by the involvement of doctors or other health practitioners.

In contrast to typical parents, the parent in this situation cannot or will not be reassured by health practitioners. The parent needs to have their belief confirmed and acted upon, but to the detriment of the child.

RCPCH Guidance states: -

“Understanding the parents’ motivation is not essential to the paediatric diagnosis of FII in the child…. important because a paediatrician is not expected to understand parental motivation, but simply to understand the cause of the child’s presenting illness.”

Child’s health and experience of health care

The child undergoes repeated (unnecessary) medical appointments, examinations, investigations, procedures and treatments. These are often physically and psychologically uncomfortable and distressing.

Effects on the child’s development and daily life

The child has interrupted school attendance and education; their normal daily life and activities may be limited. The child assumes a sick role, with the use of unnecessary aids, such as wheelchairs. The child can feel socially isolated.

Child’s psychological and health-related well-being

The child may be confused or very anxious about their state of health. May develop a false self-view of being sick. As an adolescent, they may then become the main driver of false beliefs about their own sickness, where they themselves will search for their symptoms on the internet and will remain in the role of being ill. The child may collude with their parent in an attempt to please or feel trapped in the lie about their illnesses. The child may develop psychiatric disorders and psychosocial difficulties linked to their experiences.

The severity of harm is considered in relation to the severity of the parent’s behaviours.

All practitioners who encounter children and their families, or adults who are parents, may come into contact with a child where there are suspicions of FII. These suspicions are likely to centre on discrepancies between what a parent says and what the practitioner observes. FII is most commonly identified in younger children (77% under the age of 5 years old) (Mclure et al., 1996, cited in London Safeguarding Partnership Board Procedures).

Most common

- The parent will present and falsely report symptoms and history, falsely report outcomes of investigations and other medical opinions, interventions and diagnoses;

- There may be exaggeration or misconstruing of innocent phenomena in the child;

- Invention and deception (the parent may not mean or intend to deceive, but their anxiety and beliefs are to the child’s detriment).

Less common

- Falsifying documents, through interference with investigations and specimens, such as putting sugar or blood in a child’s urine or interfering with lines and drainage bags;

- Withholding food or medication from the child;

- At the extreme end, inducing illness as a means of convincing health practitioners, especially paediatricians, that their child is ill.

Where there is a growing picture of discrepancies between the presentation of the child, independent observations of the child not backing up parental description and reports, implausible descriptions or unexplained findings and/or parental behaviours which raise concern, these should be viewed as alerting signs. Alerting signs amount to concerns for a child’s wellbeing, health, development or welfare but may in themselves are not actual evidence of FII.

Alerting signs are often seen in settings other than hospitals, including other health practitioners such as GPs, health visitors, school nurses, community nurses, and other practitioners in pre-school/early years, schools, or other educational settings.

The Children and Young People’s Law 2022 and commensurate Statutory Guidance state that practitioners must work together. Using tools such as The Continuum of Children’s Needs and the JCF chronology when working with a child and their family to support them and to understand their strengths. These tools can also be used to enable practitioners to identify needs and assess risk (JCF). The evidence gathered in a JCF multi-agency chronology is a powerful visual aid and way of seeing a fuller picture of the child’s lived experiences.

In identifying and recognising FII, practitioners need to concentrate on the interaction of three variables:

Child

The state of health of the child may vary from being entirely healthy to being sick. Practitioners may find that there is: -

- Reported physical, psychological or behavioural symptoms and signs not observed elsewhere;

- Unusual results of investigations;

- Inexplicable poor response to prescribed treatment;

- Characteristics of the child’s illness may be physiologically impossible;

- Unexplained impairment of the child’s daily life, including school attendance.

Parents/Carers

The parental view, which at one end is neglectful, and at the other end causes excessive intervention either directly or indirectly. Where parental behaviour may include: -

- Insistence on continued investigations instead of focusing on symptom alleviation;

- Insistence on continued investigations when results and examinations have returned;

- Repeated presentations to and attendance in medical settings, including Emergency Departments;

- Seeking multiple medical opinions, changing GP, paediatrician or health team;

- Providing reports from other practitioners, including those from abroad, which conflict with medical opinion;

- Also, the presence of repeated not brought to appointments;

- Parent/carer who is unable to accept reassurance;

- The Parent/carer is not following the recommended management of symptoms, despite support to do so;

- Insistence on clinically unwarranted investigations, referrals, continuation of treatment or new treatments (often based on internet searches);

- Objection to communication between practitioners;

- Frequent complaints about practitioners;

- Not letting the child be seen on their own and talking for them.

Medical view - which may be on a spectrum of feeling a need to reassure parental concerns, to feeling obliged to perform intervention or treatment.

Concerns may arise when:

- Reported any 'normal' medical condition does not explain symptoms and signs found on examination;

- Physical examination and results of investigations do not explain reported symptoms and signs;

- New symptoms are reported on the resolution of previous ones;

- Reported symptoms and identified signs are not observed in the absence of the parent;

- The child's normal daily life activities are being curtailed beyond that which may be expected from any known medical disorder from which the child is known to suffer;

- Treatment for an agreed condition does not produce the expected effects;

- Repeated presentations to a variety of doctors and with a variety of problems;

- The child denies parental reports of symptoms;

- Specific problems (e.g. apnoea, fits, choking or collapse);

- History of unexplained illnesses, death or multiple surgeries in parents or siblings of the family.

There may be several explanations for these circumstances, and each requires careful consideration and review.

Other indicators of abuse - Practitioners working with a child where there is consideration of FII should also be alert to other indicators of abuse, neglect and exploitation (see SPB Jersey Recognising Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation) and where this is the case, take action to reduce the risk of harm (see Actions).

FII is a form of child abuse and practitioners must: -

- Where there is an immediate risk of harm, call the police on 999;

- Follow the SPB Jersey Child Protection Procedures, Children and Young People Safeguarding Referrals Procedure;

- Send an enquiry to the Child and Families Hub.

Note - Immediate risk of harm from FII is rare but happens when there is true deception, such as interfering with specimens, suggesting poisoning or actual illness induction and/or concerns that discussion with the parent/carer might lead to them to further harm the child in their wish to continue their deception. In this situation, and where the child is at risk of immediate significant harm, practitioners should call the police. In cases of FII, parents/carers are not usually informed about an enquiry being placed until after the multi-agency, including Children's Social Care, Police, and a Consultant Paediatrician, have made a plan of action (please see Strategy Discussion/Meeting) as the signs and symptoms of FII require careful medical evaluation for a range of possible diagnoses. Practitioners who are unsure should seek support from their Designated Safeguarding Leads on how to manage placing a Child and Family HUB enquiry.

Please see Appendix 1: Flow Chart (Summary Diagram).

When a referral is received in relation to a child at risk of FII, children's social care should decide, within one working day, what response is necessary. All agencies should avoid delays in all circumstances.

Where a Strategy Discussion/Meeting takes place, the core agencies involved with the child must participate, where there will be decisions around the need for an Article 42 Enquiry (See SPB Jersey Core Procedures – Article 42 Child Protection Enquiries Under the Ministers Duty to Investigate).

Participants must include Children's Social Care, Police, the Lead Paediatrician or Designated Doctor, the Consultant Paediatrician responsible for the child's health, and, as appropriate:

- A senior ward nurse if the child is an in-patient in hospital or any other care facility;

- Any other relevant medical practitioner with expertise in the relevant branch of medicine where there may have been a cause for concern, i.e. specialists in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Orthopaedic Surgeons, Consultants in Ear, Nose and Throat, Radiographers (this list is not exhaustive and based on the case of the child);

- GP;

- Health visitor or school nurse;

- Staff from education settings/ nursery settings.

The lead responsibility for coordinating actions to safeguard and promote the child’s welfare lies with Children’s Services.

The Consultant Paediatrician is responsible for the child’s health care.

The police are responsible for the coordination and action taken to understand if a crime has been committed, as any suspected case of FII may involve the commission of a crime.

The Children’s social care lead, along with the multi-agency team, is responsible for the actions following the Strategy Discussion (see SPB Jersey – Core Procedures – Children and Young People Referrals, Child Protection Procedures).

At the right time, parents/carers should be kept informed of further medical assessments/ investigations/tests required and of the findings. If information would jeopardise the child’s safety and/or compromise the child protection process and/or criminal investigation, concerns around FII should not be shared with parents until it is safe to do so.

It may be necessary to have more than one strategy meeting, as the child's circumstances are likely to be complex.

Article 42 Enquiries under the Minister's Duty to Investigate

When it is decided there are grounds to initiate Article 42 Enquiries Under the Ministers Duty to Investigate [see SPB Jersey Core Procedure], decisions should be made about how the investigation and the assessment will be carried out, including:

- Whether the child requires constant practitioner observation and, if so, whether the parent(s)/carer(s) should be present;

- The designation of a medical clinician to oversee and coordinate the medical treatment of the child to control the number of specialists and hospital staff the child may be seeing;

- Consideration should be given to following the Child Protection Medical Assessment Pathway and/or Child Sexual Abuse Pathway;

- Decisions around the nature and timing of any police investigations;

- The need for extreme care over confidentiality, including careful security regarding supplementary records;

- The need for expert consultation;

- Any factors, such as the child's and family's race, ethnicity, language and special needs, which should be considered;

- The needs of the siblings and other children with whom the alleged abuser has contact;

- The needs of parent(s)/carer(s);

- Obtaining legal advice on the evaluation of the available information.

As with all child protection investigations, the outcome may be that concerns are not substantiated (e.g. tests may identify a medical condition that explains the signs and symptoms).

It may be that no protective action is required, where the family should be provided with the opportunity to discuss the support they may require.

Where concerns are substantiated and the child is judged to have suffered, or is likely to suffer, significant harm, a child protection conference will be convened.

Children's Social Care will convene an ICPC after concerns have been shared with the parents/carers and it has been agreed that to do so will not place the child at increased risk of harm. In normal circumstances, an ICPC will be held within 15 working days of the first strategy meeting/discussion, where the decision was made to initiate Article 42 enquiries.

Where FII is concerned, there may need to be a series of strategy discussions/meetings while the medical practitioners undertake continuing evaluation, and the police progress criminal investigation. Where an ICPC is held later than usual timescales, the Children’s Social Worker and their manager should record the reasons behind this in the child’s records.

Practitioner attendance at ICPC conference should be consistent with standard expectations of practitioner attendance (See SPB Jersey Core Procedures Child Protection Conferences), with additional experts invited as appropriate. As example, this may include:

- Practitioners with expertise in working with children in whom illness is fabricated or induced and their families;

- A Paediatrician with expertise in the branch of paediatric medicine, able to present their medical findings.

In some cases, legal action may be necessary before this point is reached, in which case the appropriateness of holding an ICPC will be considered.

Where a child already has a Child Protection Care Plan, and FII is a new indicator of risk for that child, consideration should be given to the inclusion of this risk in their Child Protection Care Plan and the date and time of the next proceeding Review Child Protection Conference.

Where the child presenting with FII is a child who is looked after, children’s social care will lead on actions to reduce significant harm, and their care needs will be met through their Child Looked After Care Plan (see SPB Children Looked After Living Away from Home).

All concerns and discussions must be recorded contemporaneously by both parties in their agency records for the child, dated and signed (see SPB Jersey Record Keeping).

Managing Allegations

If any concerns relate to a member of staff, practitioners should discuss this with their line manager and/or their agency's Designated Safeguarding Lead (please see SPB Jersey Multi-Agency Managing Allegations for Children).

Practitioners should have access to regular Internal agency safeguarding supervision.

Agencies should also consider multi-agency reflective supervision where cases are complex, stuck or drifting.

Professional challenges should be welcomed, and partnership working depends on resolving professional differences and conflicts as soon as possible. Where staff experience professional differences, they must follow the SPB Jersey Resolving Professional Difference/Escalation Policy.

If any practitioner considers that their concerns are not being taken seriously or responded to appropriately, they should discuss this as soon as possible with their Designated Safeguarding Lead, registered manager or senior practitioner, who should raise a concern through using the Professional Difference/Escalation process.

Flow Chart (Summary Diagram- RCPCH 2021), see Jersey Safeguarding Partnership Board - forms.

Last Updated: September 19, 2025

v33